Today on Write Better Fiction we’ll cover How the Point of View Scene Goal Relates to Overall Plot. Write Better Fiction is a process to help you critique your own manuscript and give yourself feedback. This will help you improve your novel, so you’re ready to submit it to an editor. Check the bottom of this post for links to previous Write Better Fiction articles.

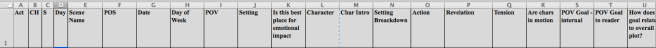

The column in the spreadsheet has long title, and if you can think of a better one let me know.

This is column where I analyze both the internal and external goal of the point of view character.

Each scene has a point of view character. This character must have a goal for the scene. If there is no goal, then what is the character doing?

Let’s deal with the external goal first. This is the goal the reader is aware of.

Finding a murderer is Kalin’s main goal throughout DESCENT. She also has goals within each scene where she holds the point of view. In the opening scene her external goal is to go skiing. Her internal goal is to be good at her job.

The reader is shown Kalin wants to go skiing. She doesn’t achieve this goal because a skier falls and is terribly hurt. She has to put her own wants aside and deal with the situation. This is the start of Kalin’s journey of searching for a murderer. At the time she doesn’t know she is witness to a crime, she’s only thinking of taking care of the skier. The external goal of skiing places her on the hill at the time the skier falls.

Kalin’s internal goal is to be good at her job. In the opening scene, she doesn’t know yet this will involve chasing a murderer.

For each scene, think about how the POV character’s goal is related to the plot of the novel. If you don’t know the answer, perhaps the scene isn’t relevant to the story, or perhaps another character should have the POV for that scene.

Your scene may just need some updating. Can you strengthen the character’s goal? Is there a way to add a goal to the scene so it relates to the novel’s plot?

You can also use this column to check for consistency. Let’s say your character is a tea drinker, and you put the character’s scene goal as finding a cup of coffee. That should trigger you’ve made a mistake.

When you’ve finished the spreadsheet for each scene, you should be able to scan this column and find any entries that are weak.

Your challenge this week is to check the previous column for internal and external character goal and determine if that goal relates to the overall plot.

I critiqued DESCENT and BLAZE using the techniques I’m sharing in Write Better Fiction, and I believe this helped me sign with a publisher.

Please me know in the comments below if you found this exercise challenging. Did it help you write a tighter scene?

Thanks for reading…

The overall goal drives the character throughout the novel. In

The overall goal drives the character throughout the novel. In  Now I’m going to ask you to use one word to name the scene. If you must, you can use two. I confess this sometimes happens to me.

Now I’m going to ask you to use one word to name the scene. If you must, you can use two. I confess this sometimes happens to me.

If you landed on number 1, give yourself a gold star and move on to the next scene.

If you landed on number 1, give yourself a gold star and move on to the next scene.