Are you struggling to make your story work?

The story arc can help you.

The story arc is made up of the Inciting Incident, Plot Point 1, the Midpoint and Plot Point 2, and the Climax.

There are those who think the story arc is a formula to follow and that it will stifle creativity. I don’t believe this. I think the story arc is about form, not formula, and it inspires me to tell better stories.

Writing a novel is a personal story arc.

Inciting Incident: You’ve been living your life, but something just isn’t right. AND THEN…your brain tells you that you need to write a story. You don’t know yet how hard this is going to be, but the world has changed, and you’re going to roll with it. So here’s the problem. How are you going to write 80,000 to 100,000 words and get people to like it?

Plot Point 1: You’ve written 20,000 words or so, spent hours doing this, and there is no turning back. You’ve invested emotion, time, brainpower and you won’t give up.

Midpoint: You’ve made it halfway. Now you really get working. Everything you have is going into the story. This is where you figure how hard it is to write a novel, but you’re determined to solve the problem.

Plot Point 2: You can’t possibly go on writing. Your structure is a mess. Everything you’ve written since the middle is making it difficult to bring the story together. You don’t know how to end the story, but you know you must work hard to finish or you’ll lose the whole story — and maybe a little part of yourself, too.

Climax: You are going to overcome your demons and finish the story. Your adrenaline is rushing. You’ve got this. You just have to fight your way through and you can write the resolution. There’s the word count you needed, and you’ve solved your problem.

I searched for an interesting way to describe the story arc. And then I found Tomas Pueyo and had to share his video.

This entertaining and insightful video will motivate you!

It’s time to stop struggling to make your story work.

Why not evaluate your story arc and see if you can make the story better? You’ve got nothing to lose by learning and trying — as long as you save your work before making large changes…

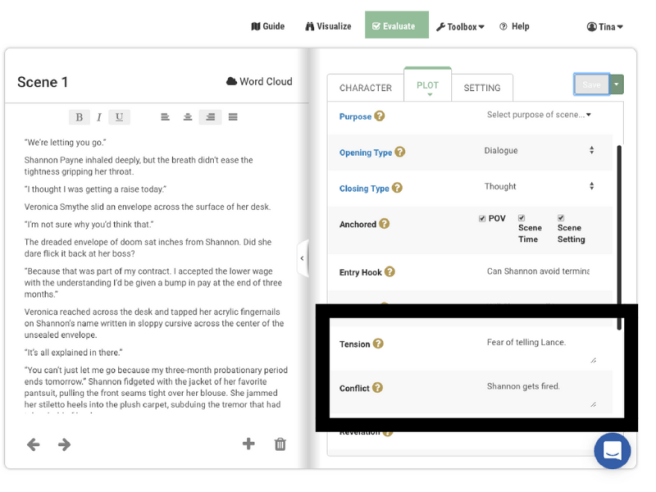

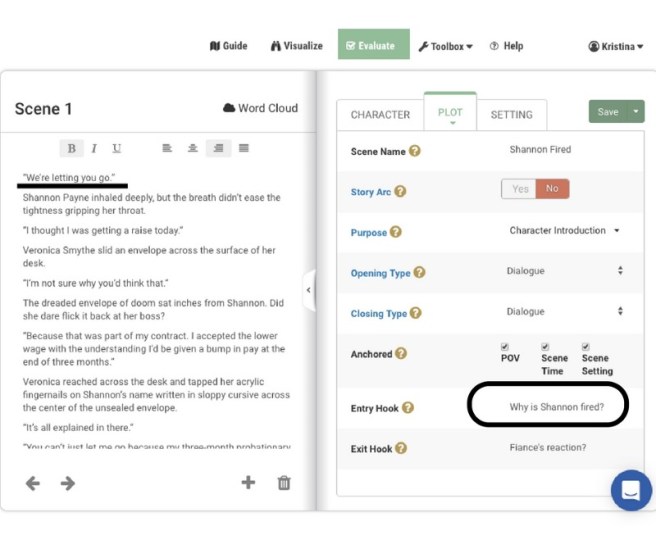

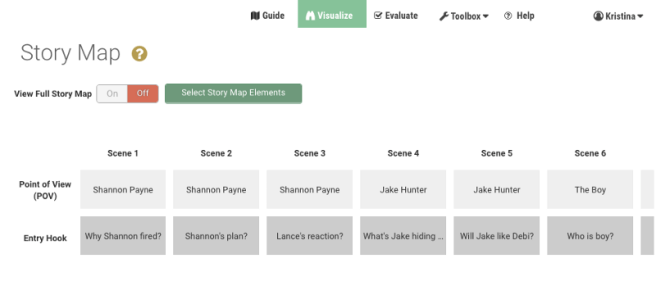

Fictionary is online software that simplifies story editing. Fictionary draws a recommended story arc and draws the story arc for your story. You can see how to improve the structure of your story within seconds.

Why not check out Fictionary’s free 14-day trial and tell better stories?

Thank you,

Thank you,