You’ve written a first draft. And with that major milestone completed, I’ll guess you want others to read your story and love it.

That means you need to take your first draft and tell a better story. One way to to tell a better story is to evaluate the story arc while you’re performing a story edit.

Today, we’ll cover the the first key event in the story arc. The inciting incident.

What is an inciting incident?

The inciting incident is the moment the protagonist’s world changes in a dramatic way.

It’s a major turning point that occurs before the midpoint of the first act. Note it doesn’t have to be the first event in your story.

The dramatic change can be positive or negative and should give the protagonist a goal she can’t turn away from.

To make your inciting incident shine, make it cause both a conscious and unconscious desire in your protagonist.

I recommend that you write your inciting incident as a dramatic scene and not as backstory or narrative summary. This enables the reader to experience the event at the same time as the protagonist and increases your chances of getting the reader emotionally involved.

The inciting incident can happen to the protagonist or can be caused by the protagonist. It’s up to you as the artist to decide what’s best for your story.

Famous Inciting Incidents

Gone Girl: Nick comes home to find his wife missing. (External goal — find wife. Internal goal — get wife out of his life.)

The Martian: Mark Watney goes missing during a storm on Mars. His teammates can’t find him, think he’s dead, and evacuate the planet.

The Philosopher’s Stone: Harry Potter receives a letter from Hogwarts and his uncle won’t let him have it.

Twilight: Bella faces the hunter as he moves forward to kill her.

Placement of the Inciting Incident

The story arc has been around for over 2000 years. It’s a proven form to keep readers engaged and is not about formula. The story, the imagination is unique to you.

The story arc is the structure of your story and the timing of the events in that story.

The arc takes the reader from one state at the beginning to a changed state at the end.

Using the tools at your disposal, like the story arc, and knowing how to write and when to place key events in your story for maximum reader satisfaction is key to a good story. So what’s a good story? It’s story others want to read.

The first of the key events is the inciting incident.

The inciting incident exists in the context of the complete story arc. If you don’t have an inciting incident in the first 15% of your novel, you need a strong reason for delaying it. Readers expect something to trigger the protagonist to act. If you delay the inciting incident, add in subplots that keep the reader engaged.

Here’s an example of a story arc from Fictionary. The brown line shows the recommended story arc, and the green line shows the actual story arc for the novel.

You can see above, the inciting incident occurs too late in the story. The writer will lose readers who get bored.

After that, plot point 1 is reached too quickly, denying the reader story depth.

And on it goes until the climax is too late, and there isn’t enough time for a satisfactory resolution. Meaning the reader won’t read the writer’s next book.

I’ll cover other key events such as plot point 1, midpoint, plot point 2 and the climax in future blogs.

I’ve love to know what you think and if you have any questions 🙂

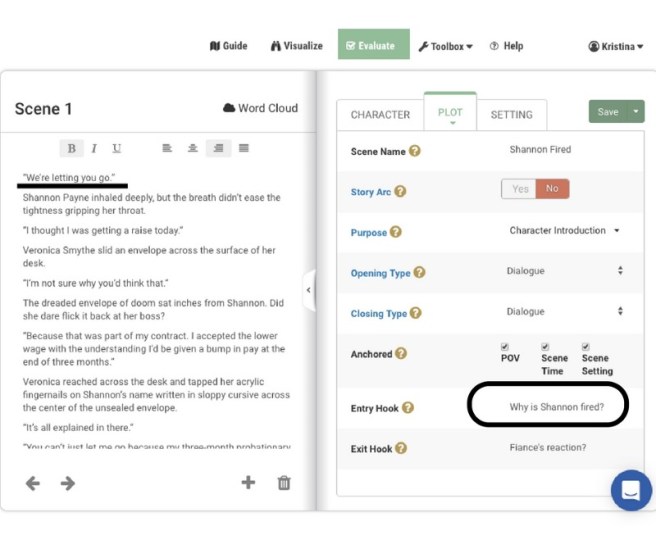

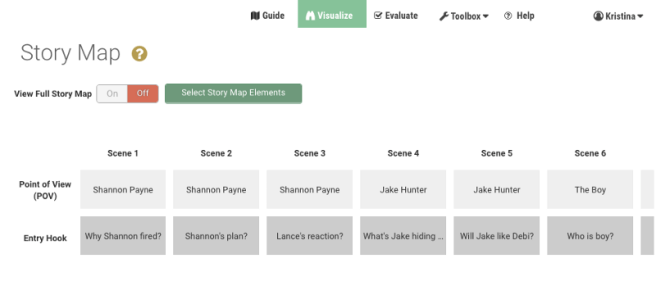

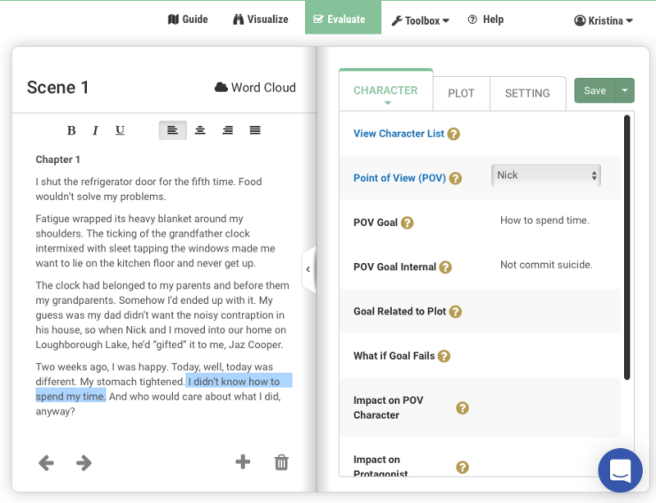

Fictionary is online software that simplifies story editing. Why not check out Fictionary’s free 14-day trial and tell better stories?

Post written by Kristina Stanley, author of Look The Other Way (Imajin Books, Aug 2017).

Kristina Stanley is the best-selling author of the Stone Mountain Mystery Series and Look The Other Way.

Kristina Stanley is the best-selling author of the Stone Mountain Mystery Series and Look The Other Way.

Kristina is the CEO of Fictionary, and all of her books were edited using Fictionary.

Thank you,

Thank you,