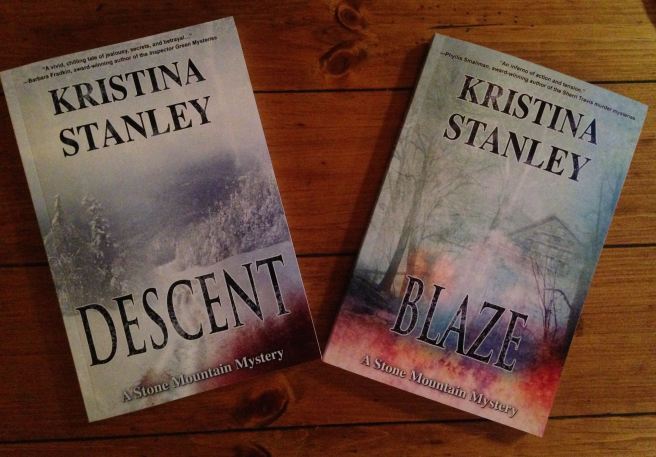

Welcome to Mystery Mondays. I’m a huge fan of the Seamus McCree novels, so it’s a great honor to have James M. Jackson share his writing advice today. I first met James when he agree to have me guest blog on his site in August 2015. James was helping me spread the word about my first novel, Descent. Over the last year, I’ve learned what generous people authors are, and here he is again being generous with his time and sharing some advice.

Is it Soup Yet? by James M. Jackson

Well, no. When I agreed with Kristina to write this blog, (thank you so much for the invitation), I was confident I would have published the next book in the Seamus McCree series. It hasn’t happened, and I’m quite happy with that because the decision was mine.

By today’s standards, I am a slow writer. There are several reasons for this. Probably the most important is that writing is only one of the things I enjoy doing. I spend considerable time each year teaching the game of bridge at my local bridge club. [In fact my first published book was One Trick at a Time: How to start winning at bridge.] I also teach an online class on self-editing/revision, and I am the president of the 600-member Guppy Chapter of Sisters in Crime.

But none of those other interests or commitments are why you can’t buy Doubtful Relations today. You can’t buy it because I don’t think it’s ready.

Readers clamor for authors they enjoy to write more books more quickly. Publishers echo the demand, even writing faster deadlines into contracts. The once-a-year-release timetable has been replaced by a nine-month regimen. Many authors now produce two books a year, and many independent authors produce three or more books a year.

This pressure for more words, more quickly, comes at a time when publishers have pulled back on the amount of sales and marketing support they provide most of their authors. Now, most published authors spend a significant amount of time performing tasks that do not directly relate to writing their next book.

Some authors have always been prolific, producing great quality writing with everything (or nearly everything) they publish. For these authors, nothing has changed. I read eighty to a hundred books a year, mostly fiction, and over the past few years, I have discovered many authors who I once loved cannot produce high-quality manuscripts with these shorter timeframes.

Storylines become flat, characters become caricatures, plot holes appear. Editors in the past would have jumped all over these problems, but shortened production schedules don’t leave enough time for major fixes. Problems are papered over. For big names, this isn’t really much of a problem: a number one bestseller will obtain huge sales with a mediocre book, or two, or three. For a less-known author, it could be a death knell.

I teach my students that in revising a manuscript, it is important to give space between the writing and the rewriting. As a first step, they should try to read their manuscript as if they were a discerning reader. When I did that with Doubtful Relations, I realized the manuscript contained two major problems: new readers to the series required a deeper understanding of prior relationships than I had provided, and I had not given the reader sufficient understanding of the motivation of the primary antagonist.

Each problem had a straightforward solution, and had I been forced to turn in a manuscript to meet an approaching deadline, I could have applied those bandages to an otherwise decent manuscript. But in thinking about those issues, I realized I could significantly improve the novel if I tore it apart and addressed certain aspects using a different approach.

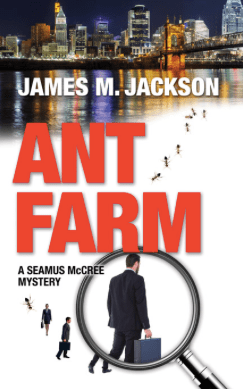

I attended a week-long workshop in 2015 run by Donald Maas, and one of the takeaways I have treasured is that sometimes the best way to fix something is to tear it down to its foundation and build it back up again. That’s what I am doing with Doubtful Relations. That’s also the approach I took with my most recent publication, Ant Farm. It started life as my first written novel. It attracted an agent’s attention and went nowhere. Frankly, it had good bones, but my writing was not yet mature. The flawed writing should not have earned an agent’s contract, and I am glad it was not published back in 2010. [I would now be very embarrassed if it had.] After being consigned to a drawer, I reread it in 2014, tore it down and built it up through a series of rewrites. When I was done, it won a contract through the Kindle Scout program.

I’m now in the process of building Doubtful Relations back up. I expect it will be available later this year. You can follow its progress (and the next two in the series that are also in the works) on my website, http://jamesmjackson.com or follow me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/James-M-Jackson-388804844542707/ or on my Amazon page http://www.amazon.com/James-Montgomery-Jackson/e/B004U7FRP2 .

Ant Farm

In this thrilling prequel to Bad Policy and Cabin Fever, when thirty-eight retirees meet a gruesome end at a picnic meant to celebrate their achievements, financial crimes consultant Seamus McCree comes in to uncover the evil behind the botulism murders.

In this thrilling prequel to Bad Policy and Cabin Fever, when thirty-eight retirees meet a gruesome end at a picnic meant to celebrate their achievements, financial crimes consultant Seamus McCree comes in to uncover the evil behind the botulism murders.

But the deadly picnic outside Chillicothe, Ohio, isn’t the only treacherous investigation facing Seamus; he also worms his way into a Cincinnati murder investigation when the victim turns out to be a church friend’s fiancé.

While police speculate this killing may have been the mistake of a dyslexic hit man, Seamus uncovers disturbing information of financial chicanery, and by doing so, puts his son in danger and places a target on his own back. Can Seamus bring the truth to light, or will those who have already killed to keep their secrets succeed in silencing a threat once more?

James M. Jackson authors the Seamus McCree mystery series. ANT FARM, BAD POLICY, CABIN FEVER, and DOUBTFUL RELATIONS (2016). Jim also published an acclaimed book on contract bridge, ONE TRICK AT A TIME: How to start winning at bridge, as well as numerous short stories and essays. He splits his time between the deep woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the open spaces of Georgia’s Lowcountry.

James M. Jackson authors the Seamus McCree mystery series. ANT FARM, BAD POLICY, CABIN FEVER, and DOUBTFUL RELATIONS (2016). Jim also published an acclaimed book on contract bridge, ONE TRICK AT A TIME: How to start winning at bridge, as well as numerous short stories and essays. He splits his time between the deep woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the open spaces of Georgia’s Lowcountry.

Carol Balawyder has taught criminology in both Police Technology and Corrections Programs for 18 years. Her area of expertise is in drug addiction and she worked in a methadone clinic with heroin addicts. She is very much interested in the link between drugs and crime and the devastating effects addiction has on the addict’s entourage. She has published short stories in The Anthology of Canadian Authors Association, Room Magazine, Entre Les Lignes, Mindful.org. and Carte Blanche. She regularly writes book reviews on Amazon and Goodreads.

Carol Balawyder has taught criminology in both Police Technology and Corrections Programs for 18 years. Her area of expertise is in drug addiction and she worked in a methadone clinic with heroin addicts. She is very much interested in the link between drugs and crime and the devastating effects addiction has on the addict’s entourage. She has published short stories in The Anthology of Canadian Authors Association, Room Magazine, Entre Les Lignes, Mindful.org. and Carte Blanche. She regularly writes book reviews on Amazon and Goodreads.

Lisa de Nikolits

Lisa de Nikolits

The overall goal drives the character throughout the novel. In

The overall goal drives the character throughout the novel. In  Now I’m going to ask you to use one word to name the scene. If you must, you can use two. I confess this sometimes happens to me.

Now I’m going to ask you to use one word to name the scene. If you must, you can use two. I confess this sometimes happens to me.